Back when I was doing my English degree, I always intended to take a class in Greek mythology. Many of the English novelists and poets we studied—and even modern playwrights—used traditional Greek stories as reference points for their works. Various professors attempted to explain various myths so we could understand the works we were studying. However, the class never fit in with my courses back then and I graduated without it.

Last semester, as I was looking for another course to take this semester—one that would not only fit into my schedule but also not conflict with my husband’s schedule or Sunshine’s preschool schedule—I started looking at Greek classes again. I am now taking Introduction to Classical Myths, the biggest class I’ve ever been in (more students than I can count!), and finding 50-minute classes very short. I’m also enjoying the material we’re studying, which provides much food for thought (when I’m not confused about all Zeus’ wives and children).

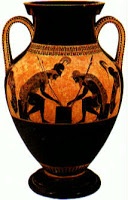

Like most other cultures, the Greeks preserved their stories first through bards and oral storytellers. Homer’s great epics were likely recited and shared orally before they were written down when a written language was developed. Much of what we know about early Greek culture comes not from letters or literature but from pictures—statues and paintings and vases. Over and over, our prof has explained to us how we can recognize certain gods by their unique characteristics—Poseidon’s trident or Hephaestus’ lame foot or Athena’s quiver of arrows.

The earliest written sources we have preserve not the myths and legends, but simple palace records. Perhaps, because of the prominence of oral storytelling, only minor things like accounts and grocery lists were written down. Or perhaps letters and stories and poems were recorded on papyrus and parchment, while simple notes were written on clay tablets that could be wiped clean and reused—clay tablets that were fired and preserved when the palaces were burned by invaders and all the parchments and papyrus destroyed.

That idea really intrigues me, perhaps for the irony of what we value and what really has lasting value. One of the concerns I have about eBooks and eReaders is their longevity. The first stories I wrote twenty years ago were saved on five-and-a-half-inch floppy disks (remember those?). Then we used three-inch floppies, then CDs, and now everything just goes on a memory stick. If I buy an eReader today, will I still be using it in five years? Ten years? What happens to all my eBooks when I need a new eReader?

That idea really intrigues me, perhaps for the irony of what we value and what really has lasting value. One of the concerns I have about eBooks and eReaders is their longevity. The first stories I wrote twenty years ago were saved on five-and-a-half-inch floppy disks (remember those?). Then we used three-inch floppies, then CDs, and now everything just goes on a memory stick. If I buy an eReader today, will I still be using it in five years? Ten years? What happens to all my eBooks when I need a new eReader?

We began our study of Greek myths by looking at background stuff—history and culture and geography. There are a lot of gaps in that, however. I find it interesting that, with all we don’t know about Greek culture and history, we do know what their stories were. We know that they called themselves Greeks because they all knew Homer’s epics, because they all told the same set of stories. We might think lightly of myths today as fantastical stories that nobody would believe—but we’re still reading them, talking about them, writing about them, studying them, thousands of years after the Greeks first told them.

Today, millions of books are published everyday. Millions of blogs spew information into cyberspace. But sometimes I wonder… what will still be around in a few thousand years, when a new generation of scholars is studying North American literature the way we study Greek literature?

Now that we’ve started homeschooling, my daughters have also enjoyed studying ancient Greece! Some of our favourite kids’ history resources include:

No Responses Yet