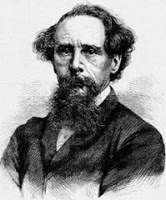

Charles Dickens had it easy. When he wrote his first novel, Pickwick Papers, as a serial story for a British magazine in 1836, the English novel as a form had only been around for roughly one hundred years. New technological developments made it easier and cheaper than ever to print books, thus making Dickens’ novels accessible to a huge (and hungry) audience. Dickens himself had a charismatic personality that, when he toured England and the United States, made his writing even more popular.

Charles Dickens had it easy. When he wrote his first novel, Pickwick Papers, as a serial story for a British magazine in 1836, the English novel as a form had only been around for roughly one hundred years. New technological developments made it easier and cheaper than ever to print books, thus making Dickens’ novels accessible to a huge (and hungry) audience. Dickens himself had a charismatic personality that, when he toured England and the United States, made his writing even more popular.

In 1830, just before Dickens launched his writing career, roughly 100 books were published in Britain. Almost two centuries later, in 2005, publishers in Britain churned out 206,000 books. I’m sure the population of Britain increased just as dramatically in that time, but it still seems to me that Dickens had it easy. He only had to build upon the work of a hundred years of novelists; his books only had to compete with a few hundred other new books.

Today’s author? Well, today’s author has three hundred years of novel-writing traditions behind him or her and has to compete with hundreds of thousands of novels being printed every year. Dickens could travel the country giving talks and acting out his novels for enthralled audiences; today’s author might do a blog tour or a few radio or TV interviews (depending on the topic of their book and their publisher’s marketing strategy).

As an aspiring writer, that’s daunting. I’m sure I could do nothing but read for the next year and I still wouldn’t have made it through all the books on my list. I haven’t read all of Dickens’ novels yet, much less novels published this year, like Esi Edugyan’s Giller-prize winning Half-Blood Blues. My fiction professor ended our workshop on Monday by urging all of us to read, read, read over Christmas. He even gave us a list of great short story collections published over the last hundred years or so. I’ll just add them to my mile-long list and get started on them when I stop weeping.

In some ways, it’s inspiring to read those early novels (Moll Flanders, anyone?) and to see how the novel has changed and developed as a form from them until now. In other ways, I feel like the writer of Ecclesiastes: “Whatever has happened—that’s what will happen again; whatever has occurred—that’s what will occur again. There’s nothing new under the sun” (Eccl. 1:9 CEB). Why should I keep writing when every story has already been written?

Because even if I write a story that’s been written before, I write it with my unique voice. I write it, as my instructor told us, in a way that only I can write it. I can learn from all those writers who’ve written before me and like them, I can try to push the novel or the short story in a new direction. Maybe my name will be lost in obscurity, like some of the other authors who published novels in 1836 with Dickens. Or maybe I’ll find a way to say something that will strike a chord with readers for years to come, the way that Dickens did.

If you had to pick a favourite novel from the last 300 years, what would it be? If you’re a writer, how do you feel about following in the footsteps of great writers like Dickens?

2 Comments

Tracy – I wasn’t thinking about computers, but you’re definitely right that if we compare that aspect of writing, we’ve got it easier. 🙂 If you think Dickens was long-winded, try Scott. 🙂

This was a thought provoking post, Bonnie. As you said, early novelists had less competition, but then think about writing a novel with a quill pen and ink! You’d want to get it nearly perfect the first time, that’s for sure!

When I read some of these early works I see how the novel has developed (for the better in many cases). I find much of Dickens work tedious in spots, and definitly long winded. My favorite ‘oldie’ is probably still Jane Austen.