After reading Becoming Mrs. Lewis, I wanted to know more about Joy Davidman Lewis. I immediately went to my library and looked up her name. Nothing. I hopped onto Amazon and tried another search. This time I found a recently published book of her sonnets and her nonfiction commentary on the Ten Commandments (with a foreword written by C. S. Lewis). Davidman’s novels were, apparently, out of print.

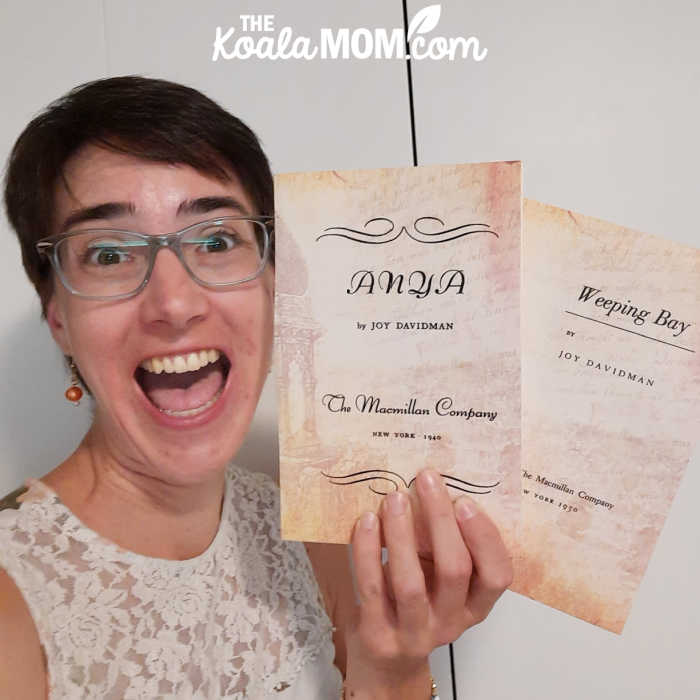

Disappointed, I let it go for a few days. Then I did another internet search. Surely there were copies of Anya and Weeping Bay available somewhere. Finally, I found a publisher in India that reprints rare and out-of-print books. I ordered both novels and sat back to wait, hoping this wasn’t some sort of scam. When the novels arrived on my doorstep within a couple weeks, I was overjoyed.

Anya plot overview

In September the appearance of Russia changed, not abruptly, but in a few weeks of sharp wind and doubtful sunlight. The summer thickness lifted from the air. Out of the horizon rose the wheat fields of the Ukraine, now harvested; they curved in endless miles of light, glittering stubble toward the eye of the beholder.

Set in the Jewish quarters of several small towns in the Ukraine, Anya is the story of a girl trying to find her place. She is twelve years old when we meet her, picking up sugar beets that have fallen from a cart, waiting for her mother to return from a trip to town. Anya is a sensitive, rebellious girl, deeply aware of the physical sensations of her body—the feel of her mother’s velvet dress against her skin, her market basket on her hip, soft candle wax between her fingers.

When Anya begins hanging out with Shimka, a young man known as a drunk who does not attend synagogue, her entire community is outraged. Her parents quickly arrange a wedding for Anya. Before it happens, Anya lets a Russian general give her a ride on his horse, throwing the entire town into scandal and the wedding is cancelled. Shimka leaves town, and Anya drifts, taking care of her father after her mother’s death.

Then a Jewish matchmaker from another town comes to her father with an offer. Anya is married to Cookeh, a gentle dry-good’s merchant. For a time, Anya is happy with Cookeh. Then her old restlessness returns. One day, she rides away from Tulchin with a Russian colonel. They spend a month at the seaside town of Odessa together. Anya rejoices in the new experiences—new clothes, new foods, new places.

Anya loved him. She loved his dilated nostrils, his wise hands with their fleshy palms that so slightly or so fiercely touched her body and burned her like a fire. It seemed to her that he had always been there; he was as natural to her as breathing, and she did not think about him.

When the colonel’s leave ends, he returns to his barracks and Anya returns to Cookeh. Despising his neighbors’ advice to turn her out, Cookeh takes Anya back again and their calm, peaceful life continues. When Anya’s next two babies are born and die immediately, the town decides this is God’s judgement upon Anya for her actions.

For a time, Anya is happy again in her life with Cookeh. Then she runs into Shimka in the streets of Tulchin and her old love for him returns.

A story of Old Russia — almost wholly detached from any vital problems of race hates and politics, though the psychological relations of the Jews and their military overlords supplies part of the basic significance of the village reactions to Anya’s departure from the Jewish traditions. It is a strange book; it is as essentially Jewish as Magnolia Street with all its emphasis on the mores; it is not a book for the conservatives, though it is, oddly enough, never gloatingly lascivious. ~ Kirkus Reviews

My thoughts on Anya

This novel reminded me of university class discussions on literary fiction vs. genre fiction. Anya is an exploration of character, a deep dive into the thoughts and feelings and actions of a Ukrainian Jewish woman who doesn’t quite fit into her tight-knit community. Davidman (who grew up Jewish) shows her deep knowledge of the culture of her people, as well as the history and atmosphere of Ukraine in the late 1800s.

Anya’s intense awareness of her own physicality and how her body is affected by the sensations around it made me wonder if she’d be diagnosed as neurodiverse if she lived in today’s world. She seems to physically feel the world around her in a way that her parents and husband cannot understand. She is constantly expected to conform, to be like other “respectable women” in Shpikov or Tulchin, to behave in a certain way. For certain times in her life, Anya does so; but then, with a blatant disregard for what is considered proper, she throws it all to the wind and follows her own emotions.

Anya is a deeply interesting character. She lives in the moment, unable to worry about the future or to regret the past. She shows no remorse for her past indiscretions, only disdain for the way her neighbors treat her because of her actions. She doesn’t seem aware of how her behavior hurts Cookeh or affects their son. She makes decisions abruptly, in a spur-of-the-moment fashion, and is barely aware of the politics or other currents swirling around her.

Davidman writes with a deep insight into Anya and the other characters in the novel, as well as the culture of their time. I loved her descriptions of the Jewish quarter, the market, the fields, the homes, the people. Even minor characters are painted with a few distinct features to set them apart. The daily life of Anya is easy to picture with concrete details about her silk dresses, her vanity, her chores at home, how she lives during her affairs.

If you’re an English geek like me, or enjoy Russian novels, I recommend trying to find a copy of Anya. It is currently available at Abe Books and in some university libraries.

More about Joy Davidman

Helen Joy Davidman was an American poet and author. She was considered a child prodigy and earned an M.A. in English literature by the age of twenty. Although raised in a Jewish home, Davidman became an atheist and communist as a young woman. She taught at university, wrote scripts for MGM, and worked as an editor for a magazine. Her first book of poems was universally acclaimed and won her several awards.

Anya was her first novel, published in 1940. Two years later, she married a fellow writer and communist, Bill Gresham. They had two sons, Davy and Douglas. Theirs was a difficult marriage due to Bill’s alcoholism, abuse and infidelity, as well as their financial struggles. After having a conversion moment, Davidman began searching for God and started a penpal relationship with C.S. Lewis.

When her doctor urged her to take a vacation for her poor health, she went to England to research a novel and to meet Lewis. Two years later, when her marriage to Gresham fell apart, she moved with her sons to England. Lewis and Davidman were civilly married in 1956, to prevent Joy from being sent back to the US when her visa wasn’t renewed, and sacramentally married in 1957. She died of leukemia in 1960 at the age of only 45.

3 Comments

Joy Davidman’s Anya “was a bird warmed by the sun between snowstorm and thunderstorm.” Rebelling against the confines of culture, Anya is marked as a harlot for her dalliances with the town rebel Shimka, a Russian General, and her betrothed Yankov. When all marital hope seems lost, Davidman introduces the character of Cookeh, nicknamed Cookeleh, whose rabbit face and dependence on his late sister temporarily endears him to Anya’s heart out of pity.

When the seven year itch of marriage sets in, Anya returns to a life of profligacy when former flame and currently married Yankov makes a reappearance in her life under the guise of letting his paramour find refuge with Anya and Cookeh while carrying out her pregnancy with his baby; meanwhile, seducing Anya again to impregnate her as well. After a stillborn birth, Anya abandons her husband, son (who her husband ironically names Yankov), and daughter for a fling with a new character Davidman introduces the disaffected Colonel Muralov, nicknamed Andre, who acquired his position by default by the death of his brother. Muralov sweeps Anya away for a month in Odessa and leaves her pregnant with a stillborn child–again! Upon her return, her little black book list comes full circle with the reappearance of none other than her first love Shimka, now living as a ne’er-do-well thief with his three brothers. He dies, but not before leaving her pregnant, of course!

Davidman constructs the chronology of Anya’s story in the Hebrew inclusio with the crux of Anya’s life marked by her marriage to the faithful if not overly attractive or intelligent Cookeh and bookended by three lovers before marriage and three paramours after marriage. Her three dead children are similarly bookended by two sons–Yankov, who has grown to despise her, and Avrom, who represents God’s reconciliation and resurrection to a new life in a new land–America.

“And as they looked back on it, behold, it was a good life; for they remembered not a month with the colonel, a year with the grain merchant, and a few months with the beloved Shimka, but seven years, four years, and again seven years that Cookeh and his wife had lived together.”

Would you be willing to sell this copy? The paperback reprints are no longer available, and I am dying to read this book!

Sorry but I really enjoyed this book and want to keep my copy. Maybe reach out to the publisher about it?