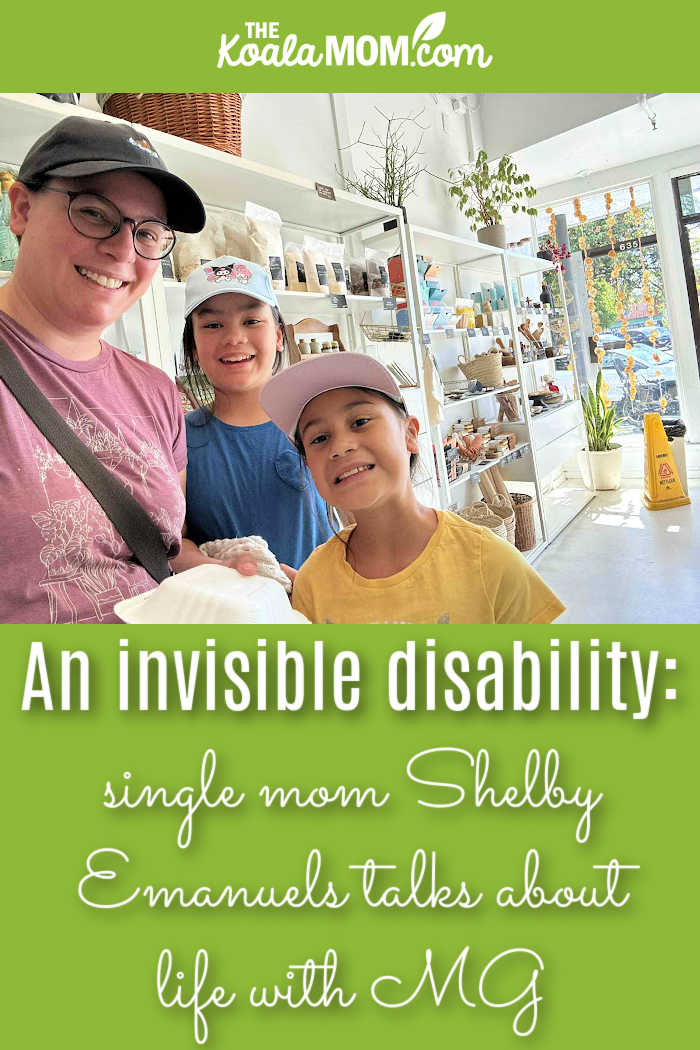

At school pickups, Shelby Emanuels is a smiling, chatty woman with a dark braid dropping to her waist. Her daughters have matching braids; her 11-year-old hovers nearby, while her 7-year-old flits about her friends. As they walk back to Shelby’s bright blue truck, it’s hard to imagine why she needs the handicap placard hanging from the rear view mirror. Myasthenia gravis is a neuromuscular condition that affects Shelby’s entire life, but it’s mostly invisible.

What is Myasthenia Gravis?

Shelby Emanuels was diagnosed with myasthenia gravis (or MG) in the fall of 2019. “That year it started with weakness in my hands and my upper lip. I couldn’t form my mouth around a straw and I couldn’t figure out what was going on. It progressed to the point where I had trouble grasping items, opening jars, and by the end of the summer, when I was walking, my left leg would go weak and my knee would give out from underneath me. I was dropping things.”

Myasthenia gravis is a rare autoimmune condition where antibodies destroy the communication between the nerve and the muscle. It causes extreme fatigue and rapid weakness in any voluntary muscle. Shelby says, “The muscles get so weak they just stop working, so I’d try to cut an apple for the kids and I couldn’t grab a knife.”

Getting a Diagnosis

For many people with MG, diagnosis takes years because the condition is so rare. Thankfully, Shelby had a family friend who was an ER doctor. He fast-tracked her to the neurology department and she was diagnosed within a month. MG does have identifiable antibodies, so Shelby had to go for bloodwork which provided confirmation of the condition. This took 3 weeks through UBC, the only place in Canada that does these tests.

After her diagnosis, Shelby was immediately started on treatment. In her kitchen, she lists off the medications she’s tried like a pharmacist. “Mestinon is my daily medication which works similar to an inhaler for asthma; it is a short-acting acetylcholine reuptake inhibitor. That means it floods my body with the communicator between the nerve and the muscle so the muscle receptors that are still working have so much more information coming to them to help my muscles work.”

Mestinon only addresses the symptoms, however, not the cause of MG (which has no cure), so Shelby has also tried other treatments. Unfortunately, her body didn’t respond to the usual first and second-line treatments for MG. Instead, she takes a heavy-duty immunosuppressant called Rituximab (a chemotherapy drug for lymphoma).

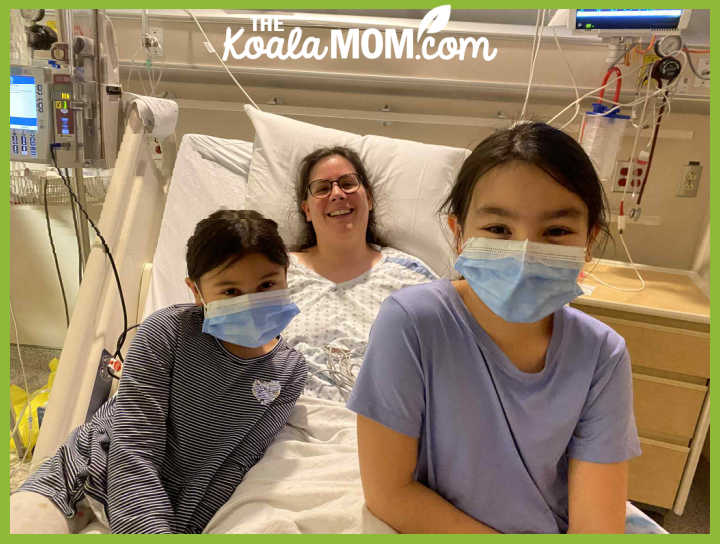

“This treatment has to be repeated every 6 months, which hasn’t been easy for me as I’m allergic to it and get horrendous side effects, but I don’t have another option at the moment. This treatment costs over $13,000 per year for just the drug, not including the nurse to administer it or the clinic time or anything else.”

The Daily Toll of MG

This fall, Shelby’s Rituximab treatment was delayed by weeks just because of paperwork. She had to get her doctor to put in an application for the treatment, which needed to get approved. Once it was approved, she could book the treatment. As six months crept into seven and then eight months, Shelby began to notice the effect of the late treatment. She was more easily exhausted. Homeschooling her girls took all her energy and strength. Housework fell behind because she simply had no energy left to do it.

“I have to choose where I spend my energy. Do I spend it on the kids’ schooling, taking them where they need to be and cooking them meals and making sure they’re clean? Or do I spend it doing dishes, tidying and putting away, doing laundry, scrubbing, etc. Because I can do one of those, not both. And my kids come first. Even then, cooking slides down the priority line. I ordered pizza last night. Leftovers tonight. But since I didn’t have to cook, I did my dishes.”

Shelby is also a single mom. Because of her MG, she can’t work and is on permanent disability, trying to juggle parenting on her own, homeschooling her girls, helping them all heal from past trauma, and her own healthcare.

Life After an MG Diagnosis

However, there is hope. Looking back, Shelby can see how much better she’s doing now than when she was first diagnosed. She says at her weakest, she had troubles holding her head up. She couldn’t walk. She had troubles swallowing food, breathing, or even talking longer than a few minutes. She would speak like someone who was deaf because she couldn’t form sounds correctly. She couldn’t even shower herself. Her youngest daughter was 2 at the time and Shelby couldn’t pick her up. She’s even been hospitalized for her MG because she was very close to needing to be intubated to breathe.

“After 6 years of getting treatment and managing my condition, MG still affects me daily by making me tired more often. I often need to have naps. I need to rest more often. If I do something repetitive for too long, I get weak in that area, so I’m limited to how much I can do in a day. Any repetitive behaviour will cause that muscle to get tired. If I walk too much, my legs give out; if I use my hands too much, my hands go weak and I can’t use them. I can’t even drive too long because my eyes get tired and I can’t see properly.”

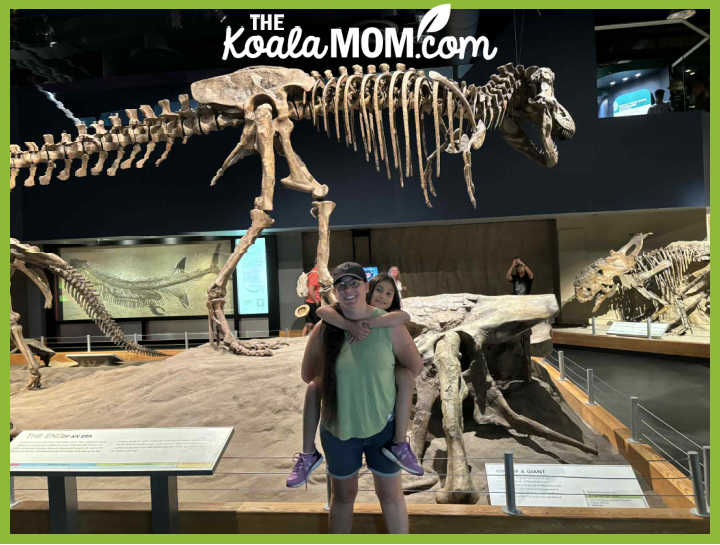

This summer, Shelby took her daughters to visit friends in Alberta. They spent a day at the Royal Tyrrell Museum in Drumhellar. Her 7-year-old has ADHD and needed a lot of help staying focused on each exhibit instead of running ahead to the next one, so Shelby piggy-backed her to slow her down and give her older daughter time to read each sign.

“This wore me out and I could barely walk when we got back to the car. Later when we went to see the hoodoos, I was unable to walk around the hoodoos with the girls. I had to wait on a bench while a friend of mine took the girls through. That friend also took my 11-year-old daughter up the T-rex, because I couldn’t climb the stairs there.”

An Invisible Disability

Since getting her diagnosis, Shelby has had to learn to speak up for herself. Because MG is an invisible condition, people assume she can do everything. “I’ve often had to ask for help around my house with basic tasks other people take for granted. I’ve had friends drive me to appointments. I’ve hired someone to help me clean my house.”

Little things like where she can park can make all the difference in her life. “I have a handicap parking placard, but sometimes I get funny looks or dirty looks. Having that closer parking spot helps me to be able to actually go shopping on my own because I can park closer, go in and get what I need, and get to my vehicle more easily. I do a lot of online shopping and grocery orders or grocery pickup.”

Self-Care Matters

Besides advocating for herself, Shelby has also had to learn self-care. “I’ve had to learn to recognize the beginning signs of being weak and rest, regardless of what needs to be done in the house or socially or with my children. I have to prioritize taking care of myself and let go of the guilt of resting when dishes need to be done or laundry needs to be done and the bathroom is dirty or the kids need to get outside.”

This hasn’t been easy, because before her diagnosis, Shelby was an active, independent young woman. She was involved in cadets as a teenager and enjoyed camping and hiking. Now, she can’t do those things or has to be careful about how she does them. As a single mom, she also deals with a lot of mom guilt over what she’s able to do for her girls and how her house looks.

“Sometimes I have to rest for a whole day and battle the guilt of not having a clean house or not having the dishes done. It’s hard to rely on people to do the littlest things for me. I had to ask my sister-in-law to come make the bed for me one day because I couldn’t even do that.”

Community Makes a Difference

Shelby Emanuels has found support and encouragement through the Myasthenia Gravis Association of BC. They have peer support, general meetings with keynote speakers, and a bi-annual newsletter. Shelby’s story was featured in the Spring 2024 newsletter, where she talks more about the treatments she’s tried and shares her advice for others suffering from MG.

Shelby’s story is a reminder to all of us that we never know what someone else is going through. A person who looks healthy and happy may be struggling with an invisible disability or disease. Her story is also a testament to her strength in advocating for herself, taking care of herself, and finding hope in the face of a difficult disease.

No Responses Yet