For Throwback Thursday, I thought I’d share a piece I wrote about a town in Australia I visited about nine years ago today.

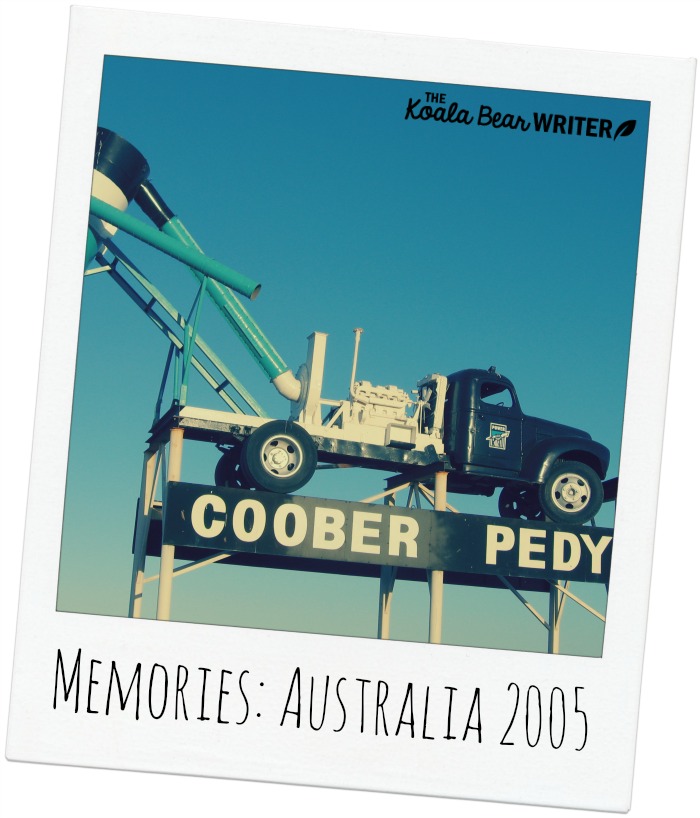

Coober Pedy, Australia, is a ramshackle, helter-skelter town built out of bits and pieces on piles of dirt. There are no green lawns, no trees or flower beds—just red dirt or creamy sandstone. Most business names begin with “underground” and most have something to do with opal.

I had been warned that Coober Pedy was “different,” though nobody quite told me what they meant by that. It is one of few towns between Alice Springs in the middle of the outback and Adelaide on the coast of Australia and one of the overnight stops for any tour traveling between Alice and Adelaide.

For hours before reaching Coober Pedy, our tour group drives through land that is flat and red.

“What do they eat?” Jules asks me, pointing to some emus running away from our van.

I shrug. I can’t see anything that resembles food, but we’ve seen kangaroos and dingos as well as the funny-looking birds that can outrun our van.

Jules is from Wales and I am from Canada, but we are both traveling alone for this trip and so find some companionship together. There’s been little to talk about for a while, though, as nothing in the scenery has changed. Then I see something that makes me look again. A line of green eucalyptus trees stretches away toward the horizon.

Wendy, our tour guide, senses the question sprouting in our heads. “The trees are growing where the river is,” she calls over the noise of the bus. “But don’t expect to see water there—it’s all underground, like everything else in Coober Pedy. You’ll have to dig to find it.”

As we get closer to town, she explains why it’s called Coober Pedy. “The name’s an English attempt to pronounce an Aboriginal word. The Aboriginals looked at all the underground houses here and called this place ‘white man’s burrows.’”

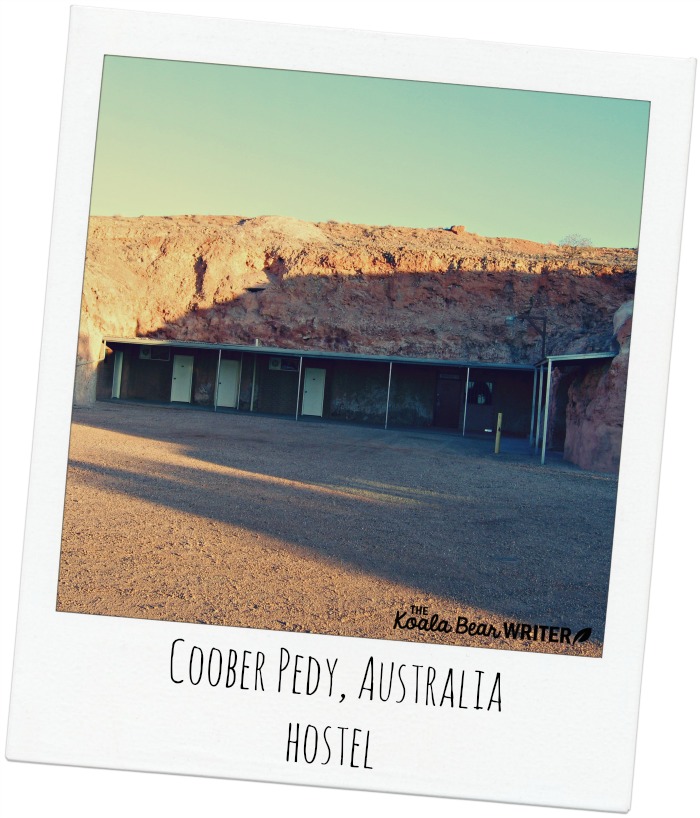

It’s an apt name, for seventy percent of the population live underground. Even the hostel we stay in is underground. The walls, ceiling and floors are smooth, varnished sandstone. Our bunks are wooden, with curtains hanging across the doorways. And it is warm. Nights in Australia can get cool, especially in the outback, where temperatures might drop to zero degrees Celsius. Thinking of Robert Service’s Sam McGee, I tell Jules, “Coober Pedy’s the first place I’ve been warm all night since I came Down Under.”

Historically, the town itself is one of those “accidental” discoveries. A party of prospectors were wandering around the outback in 1915, unsuccessfully searching for gold. At the end of one day, they set up camp and went looking for water. A 14-year-old boy in the group found pieces of opal on the ground, and eight days later, the first opal claim was made. Two years later, the railway was completed and brought construction workers and soldiers returning from World War I. They were the first to live underground because of the harsh conditions. The name appeared in 1920, replacing the previous name that acknowledged John McDougall Stuart, the first European explorer to the area in 1858.

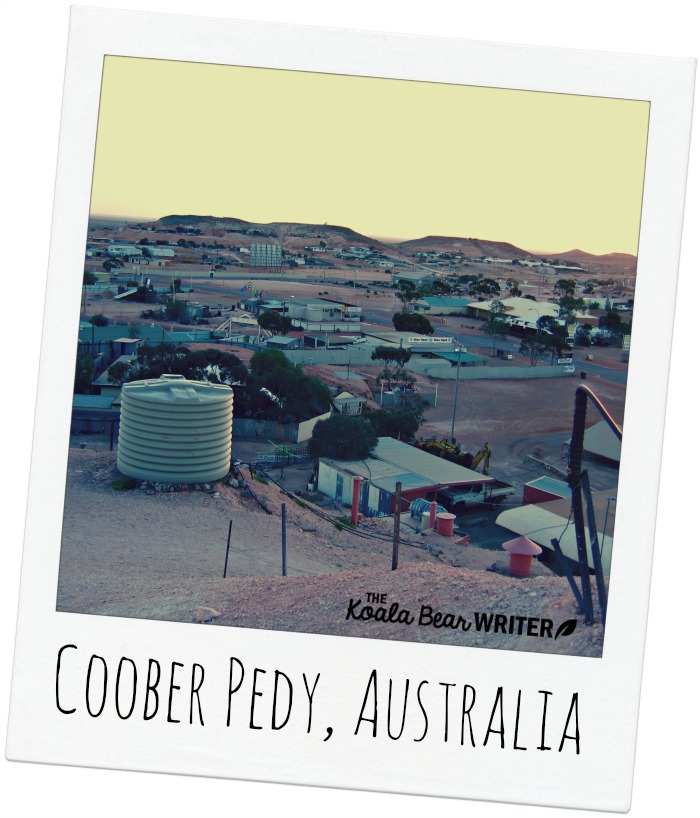

As Jules and I stand on top of one of these opal mines and look out over the town, we wonder that anyone would want to live here. Any buildings above-ground are short and old. There is a pizza parlour where we eat supper, several churches, a few pubs and liquor stores, many opal mines, a post office and hospital, convenience stores.

It’s a hilly town, with doors in most of the hills, leading to the businesses or homes under those hills. Otherwise, it looks like a junkyard, with pieces of things—water barrels, vehicles, mining equipment, and other stuff I can’t identify—laying around.

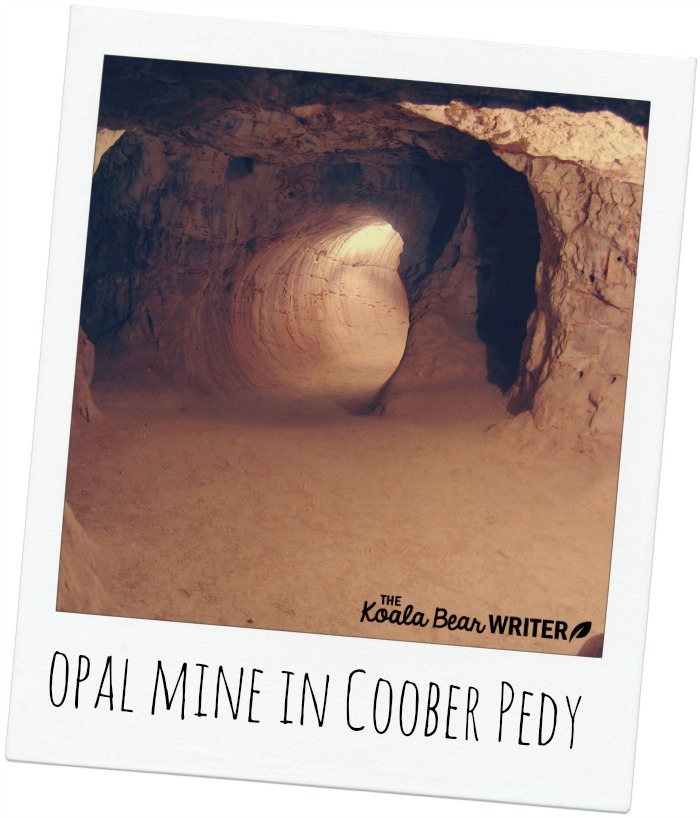

After settling into our hostel, we take a tour of an opal mine. We see a video replaying that first opal discovery and then explaining opals and opal mining. We wander through the smooth, round sandstone tunnels carved in pursuit of the pretty stones. In one place, some opal has been left in the wall so we can see what it looks like before it is mined and polished—a seam of dark, smooth stone within the rough, light-coloured sandstone.

We move from the dusty, round tunnels of the mine to the polished square rooms of an underground house. The natural beige colour of the sandstone gives the room a cosy feeling, and again, I notice the temperature. “Underground is warm in winter, cool in summer,” our guide boasts.

Back in the opal mine, Jules and I peruse the jewellery. She tries on some bracelets while I look at the earrings. My aunt told me to buy some opal on my trip, because Australia is known for its opals. Here at the source of the precious stone is a good place to do that, I decide, but it’s hard to choose. There is sparkling white opal, dark blue opal, glimmering green opal. Big and small, set in silver and gold, bracelets and necklaces and earrings and rings, and even carved opal figurines.

“Blue is the most common colour, and red is the most rare,” the girl behind the counter tells me.

I turn the stones, seeing how they catch different colours in different lights. As I study them all and finally pick a pair of silver earrings set with green-blue opals, I catch a glimpse of what drives people to search for these stones. Each stone is different, flashing its own colours at the observer. A diamond is always clear and a ruby is always red, but an opal may be white or yellow or green—and yet it will flash every other colour at you as well.

After supper at the pizza parlour, Jules and I walk back over the opal mine to our underground hostel. The sun is setting on the horizon, making the desert seem even more red. There’s nothing here except opals, I think, and the people who come here to chase them or to get away from something else. Yet somehow, I understand why people elsewhere could only describe Coober Pedy to me as “different.” There are no words for a town like this, perching in a place where it seems that nothing should be able to survive—a town that has carved out its own unique existence and flourished in its own way.

8 Comments

WOW! What an adventure! I have always wanted to go to Australia ! It looks like such an interesting place to visit! What a neat town, although I don’t think that I could live underground!!! Too scary for me!

I loved my time in Australia and would love to go back again someday – I only saw about half of the country. There’s so many neat places to see. 🙂 I’d definitely go back to Coober Pedy and try to explore more than we had the chance to on this tour. 🙂

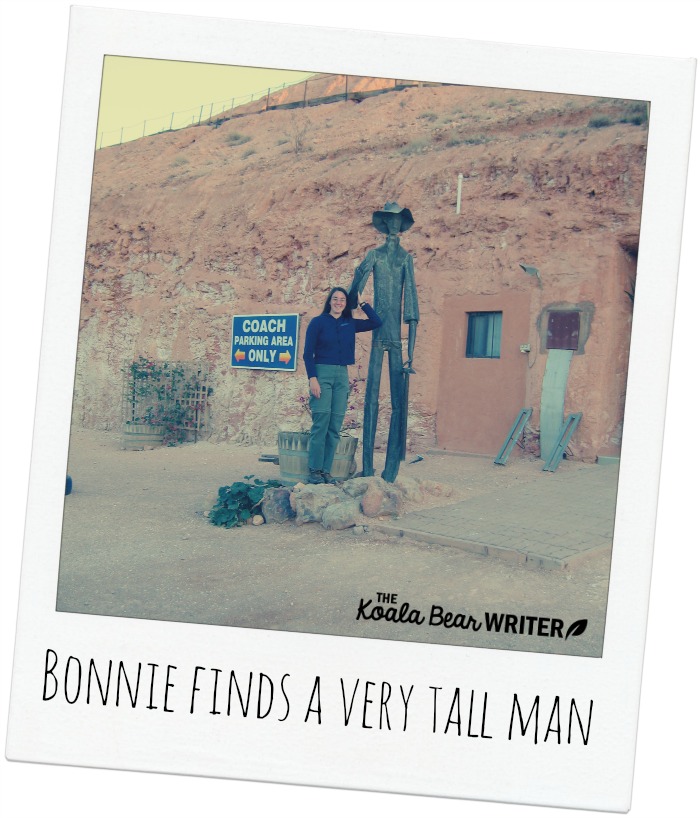

Haha, I see you found the love of your life 😉 lol I have never been to Australia, but I have always wanted to go. I would just need to be knocked out for that flight or I would be a nervous wreck.

Randa – I’m 5’10” and most of the guys in my family are tall. 🙂 Yeah, the flight is really long. I slept most of the way there as it was overnight but coming back was during the day and I think I read a lot. Or watched the inflight movies. 🙂

oh those tunnels look amazing! I also found Australia very cold when I was there during July/August and I made sure to bring some opal home too, a necklace for my mom!

Yes! We think of Australia as hot but July/August is their “winter,” which I found more comparable to Canadian spring/fall (or even summer) temperatures. I don’t think I’d go there for the summer! 🙂

What a cool place to find when on an adventure! I have never been to Australia, but hope to go someday. It would be neat to check out these places that time forgot. What a discovery! Great story Bonnie..

I hope you make it someday! Although I recommend doing some research ahead of time and prioritizing the places you want to see – it’s a big country! 🙂