Last semester, my creative nonfiction class read Myrna Kostash’s “Open Letter to George Ryga,” a hilarious and interesting essay about (ironically) book reviews. While I’m not familiar with George Ryga, the idea of an author inviting a reviewer out for coffee to ask her why she didn’t like his books seemed audacious to me. On the day we discussed this essay in class, Myrna was there to talk to us about writing creative nonfiction, which she’s been writing since it first emerged as a genre in the 1970s.

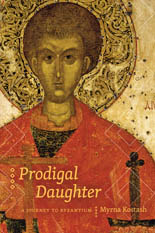

So when I was reading a local Catholic newspaper a few weeks later and saw Myrna’s name along with a request for reviewers for her latest book, I quickly emailed the University of Alberta Press asking for a copy. Prodigal Daughter: A Journey to Byzantium landed in my mailbox a few weeks later and I started reading it over my Christmas break. It went to Alberta and back with me, and I’ve tried to pick it up again a few times since we’ve been back. But I haven’t finished it.

So when I was reading a local Catholic newspaper a few weeks later and saw Myrna’s name along with a request for reviewers for her latest book, I quickly emailed the University of Alberta Press asking for a copy. Prodigal Daughter: A Journey to Byzantium landed in my mailbox a few weeks later and I started reading it over my Christmas break. It went to Alberta and back with me, and I’ve tried to pick it up again a few times since we’ve been back. But I haven’t finished it.

Somewhere in the first half of the book, Myrna lost me. Maybe it’s because I was too tired and missed something critical in the first few chapters. Maybe it’s because I usually read while nursing Lily and listening to Sunshine’s nonstop chatter. Maybe it’s because I’m not really familiar with eastern European history.

There have been parts of the book I’ve really enjoyed. Some great stories, some great writing. The book itself is a beautiful book—the kind of book you just want to hold and stroke. This isn’t a cheap, poor-quality paperback. It’s got a lovely smooth, soft cover and thick pages. I’m quite impressed with what a small university press can produce.

However, as I said, the story lost me. Most of the book has been about Myrna searching for Saint Demetrius—though why she’s so interested in him I’m not sure. The story jumps around between her various trips to Greece (I’m not sure how many times she’s been there) and other countries in Eastern Europe and her time spent at home in Canada (mostly near Edmonton, Alberta). There’s also big leaps in time, as the story starts with her childhood in the 1950s, goes to 2000, and then jumps back to various years in between. Most of these leaps are clearly indicated, but it still left me confused as to a timeline for events. When was she where and what questions lead to other questions?

Perhaps it was the subtitle, “A Journey,” that lead me to expect more of a storyline, some sort of logical progression through her questions and answers, rather than this leaping around in time and place. While I learned more about eastern Europe than I’d known before, I felt like I had no framework within which to fit this information and why it mattered to Myrna, much less to me.

So while I dislike not finishing a book that I’ve started, I’m afraid that’s what I’m doing. I’m going to send Prodigal Daughter to a friend of mine who is Russian Orthodox, in the hope that, since she knows more about the topics discussed in the book, it will make more sense to her. And maybe I’ll check out some of Myrna’s other books or shorter works. Prodigal Daughter, however, left me confused and disappointed.

This book was provided for review by the publisher.

No Responses Yet